Expert view

Ethiopia

7 May 2021

How coffee and carbon credits cut deforestation in Bale, Ethiopia

By Dr Yvan Biot, Senior Associate, Farm Africa

Sack upon sack filled to bursting with finest quality organic Arabica coffee have just been piled high on the back of a lorry in the depths of the Harenna Forest in the remote Bale Eco-region in Ethiopia.

Their ultimate destination? Cafés and shops across Europe, US and Australia, where the beans will be savoured by coffee lovers keen to enjoy this heirloom variety of wild forest coffee from the crop’s birthplace.

In total, cooperatives supported by Farm Africa in Bale sold 40 tonnes of coffee to the international speciality coffee market this spring, a more than fourfold increase on the 2020 total of 9.35 tonnes.

This is cause for celebration for communities living in Bale, where poverty is rife.

Farm Africa’s support in connecting the cooperatives to global markets offers local people the opportunity to build sustainable livelihoods, as Mr Abdurahiman Kule, Chairperson of Gutity Cooperative, explained:

“We are highly motivated to produce coffee with higher quality. This will grow the income of cooperative members, improving our lives.”

Farm Africa’s support for the coffee cooperatives in Bale was made possible by the organisation’s long-term engagement in the Bale Eco-region, which aims to develop forest-friendly livelihoods such as coffee production.

Protection of the forest in Bale is more urgent than ever as high population growth and low agricultural yields are leading to deforestation to make way for an expansion of the smallholder agricultural frontier.

Livelihood opportunities for remote communities living in the proximity of those forests are few and far between and unless we find ways to make it worth their while to protect forest resources, they will be converted into farmland.

While coffee production is part of the solution, the scale of the threat to the region’s forests calls for a multi-pronged approach. Enter REDD+. In 2012, and OFWE, the Oromia Forest Management Agency, helped the local community establish a REDD+ scheme to enable them to earn additional income from the sale of carbon credits for avoided deforestation. Local communities play an important role in forest monitoring, management and sustainable production through their forest by-law agreements.

What is REDD+?

REDD+ stands for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. First conceived at the beginning of the century, the scheme aims to remunerate forest dependent communities and businesses for their provision of environmental services that are essential for the nation or the global community.

Part of a wider set of “Payments for Environmental Services” and a standard-bearer for “nature-based solutions”, one of the UK’s five priorities for COP26, the core principles of REDD+ are simple: for each hectare of forest a farmer, government or business decides not to convert into farmland, rangeland or plantation, a payment is made that represents the value of the environmental service provided – in this case: avoided carbon emission.

The devil, as usual, is in the detail. The approach our technical team adopted in Bale consisted of establishing what might happen in the absence of any effort to slow down deforestation. This ‘projection’, also referred to as the ‘baseline or business as usual rate of deforestation’ mirrors the approach used by the scientific community to establish business as usual climate projections for policy development. And as in the case of climate policy analysis, such projections are not crystal balls of the future but rather benchmarks used for decision making.

Establishing the baseline rate of deforestation is a lengthy process that relies on expert analysis of satellite imagery and tedious fieldwork to check that the algorithms developed for the estimation of forest cover from satellite images represent the reality on the ground.

Once established, the results were used to better define the target areas for intervention and establish the benchmark against which to compare future deforestation.

Decision-making on the basis of projected futures is only as good or as bad as the data and models used for predicting the future. The results are highly dependent on the approaches used and are open to interpretation. This is why strict protocols for making such projections are developed and agreed by multiple stakeholders, involving strict guidance on how to measure and assess forest cover, carbon content and baseline deforestation rates, and how to convert reduced deforestation into carbon credits. The process is subjected to a rigorous independent audit and public consultation.

For the Bale REDD+ project, we adopted two standards developed by NGOs and businesses: the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), managed by not for profit company, Verra, and the standards issued by the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA).

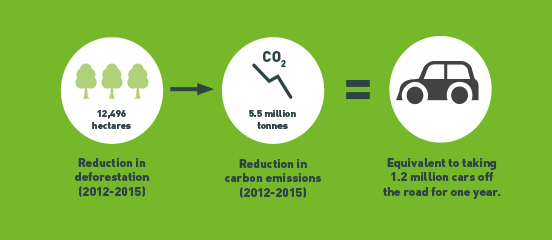

In 2017, Verra awarded a total of 5.5 million tonnes CO2-equivalent credits to the Bale REDD+ project for reduced deforestation in the project area between 2012 and 2015.

While these credits are being sold on the voluntary carbon market, the team has initiated the verification of further emission reductions from reduced deforestation between 2016 and 2019. Once completed, the proceeds from the revenues from these sales are distributed to the local communities and the forest management agency in Bale according to a 60/40 benefit sharing agreement.

Is REDD+ foolproof?

Carbon credits from reduced deforestation generate debate. Some argue that off-setting emissions by, for example, airlines, for failing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the first place doesn’t achieve ‘real’ emission reductions.

Others argue that the use of ‘business as usual deforestation’ predictions does not sufficiently protect ‘buyers’ from ‘sellers’ inflating project achievements. And with forest cover being derived from satellite imagery, there is ample scope for data wars between proponents or opponents of one or another estimation system.

There are also serious risks of avoided deforestation rates in one region triggering increased deforestation in adjacent areas, a process referred to as ‘leakage’. It is precisely to protect the ‘market’ against those potential risks that VCS and CCBA were developed, through a lengthy process involving NGOs, indigenous people organisations, governments, businesses and scientists. And when applied correctly, checked and counter-checked by our technical teams, the systems developed by the VCS and CCBA communities have proven resilient to contestation from multiple interest groups.

The future of REDD+ in Bale

As with all innovations, it is likely REDD+ will develop further, both in terms of technologies for estimating carbon benefits and protecting the scheme against the risks of inflated claims and leakage.

One such development involves extending the target region to a whole country or region within it, and to adopt protocols agreed within the UN system, supported by rigorous scientific analysis and verification.

The Ethiopian government is piloting this approach through the development of its ‘jurisdictional’ REDD+ project covering large parts of the Oromia and SNNP Regions, with assistance from the World Bank and the Bio-Carbon Fund. Farm Africa and its partners SOS Sahel and OFWE are very proud to have been able to pilot the REDD+ approach in Bale, with assistance from the Norwegian government, and to share lessons with the team responsible for the development of this nation-wide approach.

Our current efforts are aimed at ensuring that the benefit schemes we have secured for the local communities in Bale are included in the new scheme, within which the Bale REDD+ project will from now onwards be embedded.

This will mean that farmers’ cooperatives like the one Abdurahiman Kule chairs will be able to count on not just income from their coffee, but also on the economic rewards that their hard work managing the forest around them will continue to earn. This is good news not just for the cooperatives, but for all of us due to the importance of forests in achieving the Paris climate agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

Whatever the reasons for being cautious about offset markets in general and REDD+ in particular, the fact remains that if rich countries want forest-dependent communities in tropical countries to protect forests to help mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and protect biodiversity, ways need to be found to remunerate those communities for these services. REDD+ in its various and evolving forms is still the front runner in the search for equitable transfers of resources to incentivise nature conservation and Farm Africa remains committed to assist the global community in this endeavour.

About the author: Yvan, a tropical agronomist with a PhD in development studies, managed the research team in Manaus, Brazil, which established the first field measurements of biomass and carbon content of central Amazonian forests. In Indonesia he directed multi-stakeholder forest governance programmes that laid the foundations for decentralised, community-based forest stewardship. In his subsequent posting as Senior Climate and Environment Advisor with DFID, he helped develop direct access modalities for UN climate funding to Developing Countries and participated in the establishment of the WB Climate Investment Funds. Yvan assists Farm Africa in issues related to forest management, REDD+ and natural resource management and, as a Fellow of the Samdhana Institute, remains closely involved with community-based forest management initiatives in South East Asia.