Expert view

21 March 2016

A history lesson through the prism of Chilimo forest, Ethiopia

Blog by Michelle Winthrop. Follow her on Twitter: @M_Winthrop

Today, 21 March, is International Day of Forests, a day that highlights the importance of forests to human development, biodiversity and climate change mitigation.

It’s a fitting day for me to reflect on my recent short visit out of Ethiopia’s capital city Addis Ababa to visit Chilimo forest, where Farm Africa is supporting community forest groups to produce and market sustainable timber.

As someone who studied history at university, I always enjoy a good local history story, especially as it relates to wider world developments. But little did I expect such a rich history lesson from Chilimo.

As one of the few remnants of dry Afro-montane forest that remain on Ethiopia’s Central Plateau, Chilimo carries huge environmental significance, as well as historical interest.

The forest community here has been witness to some fascinating moments in Ethiopian history.

Emperor Menelik II (who ruled Ethiopia from 1889-1913) first recognised the importance of the forest,which then covered some 22,000ha. In an effort to conserve it, he introduced what some refer to as Ethiopia’s first forest laws, proclaiming that all forest trees belonged to the government, and that royalties were payable to the government for their use.

But his conservation efforts were thwarted by the subsequent changes in ownership of the forest.

Menelik II gave the forest as a gift to a French citizen as a favour for providing war weapons (all we know is his name was Komdor), who managed it carefully, until handing over to Ras Makonnen, who in turn passed it to Emperor Haileselassie.

During Haileselassie’s time, a beautiful building was constructed in the forest, which went on to be the Farm Africa field office from 1991. As a reward for bearing him a son, Leul Makonnen, Haileselassie granted the forest to his wife, Empress Menen in 1923. Unfortunately, she leased it out to private companies who engaged in intensive logging (bringing the total coverage down to 12,000ha).

During Haileselassie’s time, a beautiful building was constructed in the forest, which went on to be the Farm Africa field office from 1991. As a reward for bearing him a son, Leul Makonnen, Haileselassie granted the forest to his wife, Empress Menen in 1923. Unfortunately, she leased it out to private companies who engaged in intensive logging (bringing the total coverage down to 12,000ha).

The communist Derg regime that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1987 recognised the importance of the forest, but their solution was to place armed guards around it to prevent communities logging further. These efforts failed to prevent further clearance of the forest for logging, firewood and agriculture and between the Derg regime, and the early years of the current government, where management was limited, the forest was depleted to less than 5,000ha.

In 1991, the first Farm Africa pilot introduced the concept of Participatory Forest Management (PFM) to Chilimo forest, an approach that emphasises joint partnerships between local forest communities and government. PFM gives local people an economic incentive to sustainably manage and protect forests by helping them set up forest-friendly businesses such as sustainable timber production.

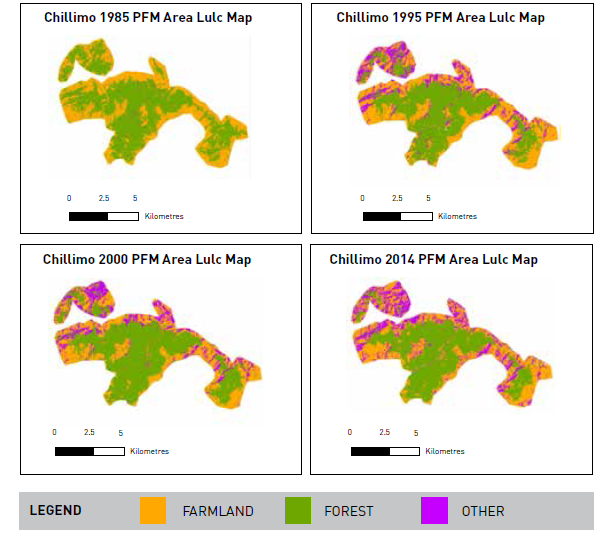

Community and forest cooperative leaders Ato Tessema, Ato Abera, Ato Ashibru and W/ro Seregatu were clear during my visit in telling me that ‘Farm Africa saved the forest’, which is now thriving at 5,000ha. The impact that PFM has had in halting, and even reversing deforestation, in Chilimo is impressive, as seen by this satellite imagery.

Over the years, the model of joint community and local government management has gone from strength to strength, and Farm Africa’s support was no longer needed after about 2007.

However, last year, we approached the Chilimo community and asked if they might be willing to pilot a community-managed timber plantation, with the support of the Ashden Trust.

In recent years, the community had been planting eucalyptus, but Farm Africa’s support has enabled them to produce more seedlings from their community-managed nursery, and trained them to plant a variety of trees (fast-growing eucalyptus alongside slower-growing and higher-value grevillea robusta, pine and cypress), on fields previously producing crops.

Already these efforts are starting to really pay off financially as well as environmentally. One of the 12 Chilimo cooperatives generated a dividend of ETB1,300,000 (about £43,000) this year. This was distributed to members after contributions were made to the cooperative saving scheme and other community investments.

Already these efforts are starting to really pay off financially as well as environmentally. One of the 12 Chilimo cooperatives generated a dividend of ETB1,300,000 (about £43,000) this year. This was distributed to members after contributions were made to the cooperative saving scheme and other community investments.

One family that participated very actively in PFM by organising members, monitoring for fires, and so on, has obtained a payout of about ETB12,000 (about £400).

It is clear this activity has huge potential. Ethiopia has a huge unmet demand for wood, for furniture, for construction in the rapidly expanding cities, and for utility poles.

Finally, this community is being rewarded for their decades of work preserving their forest.

There is work to be done, to help them grow more, develop the nursery into a profitable endeavour, attract investment so they can add more value to the wood, and help strengthen the cooperative union.

But the enthusiasm is palpable – W/ro Seregatu has moved to the nearby town to be with her older children. This has enabled her to plant more trees on her land, and she is generating income and, she believes, investing in a legacy for future generations. ‘I will never stop planting until I die’, she told us. Inspiring words indeed, which gave me encouragement that remote communities like hers can turn forest management into a profitable pursuit. That’s something that benefits all of us, no matter where we live.

UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, said of forests: “To build a sustainable, climate-resilient future for all, we must invest in our world’s forests. That will take political commitment at the highest levels, smart policies, effective law enforcement, innovative partnerships and funding.”

And that’s just what’s happening right now in Chilimo, one eucalyptus sapling at a time.

It is exciting to know that a forest with such a rich and interesting past has such a potentially lucrative future, and that Farm Africa will be there with the community every step of the way. I’m sure Emperor Menelik II would have been proud.