Expert view

11 December 2015

The view from Paris: what climate change means for smallholder farmers

Exhausting as it is to be living out of a suitcase, I feel fortunate that my current trip to Paris to attend side events at the COP 21 climate change talks follows hot on the heels of a visit to rural Ethiopia.

Just ten days ago my home for a few days was Halaba in Ethiopia’s SNNPR region, a remote small market town a world away from the bustling boulevards and bistros of Paris. Nestled in rolling hills, Halaba is surrounded by village after village where smallholder farmers living in traditional thatch-roofed round houses try to eke out a living for their families cultivating small plots of land.

I knew before my arrival in Halaba that the area was gripped by the ravages of drought, but I was unprepared for its severity. Younger farmers trying to cope with multiple crop failures told me they had never seen anything like it. Older ones said this year’s drought is as bad, if not worse, than 1985’s.

With these words still ringing in my ears, I arrived in Paris with renewed determination to play my part in standing up for smallholder farmers across Africa: people who have done so little to contribute to climate change but are the ones suffering so much from its effects.

Climate trends

While the extremity of the drought in Halaba is no doubt exacerbated by this year’s exceptionally strong El Niño event, it’s clear that even in non El Niño years, global temperatures are on the rise. And while this has been contained to just short of 1⁰ in the past 40 years, if we continue to burn fossil fuels at the current rate, global temperatures could rise by as much as 4⁰ by 2090.

It’s not just tempera tures that are affected – rainfall has been increasing in intensity across East Africa since 1960, and while in some parts of the world climate models predict higher rainfall and an increased probability of flooding, in others parts drier conditions and more frequent droughts are expected.

tures that are affected – rainfall has been increasing in intensity across East Africa since 1960, and while in some parts of the world climate models predict higher rainfall and an increased probability of flooding, in others parts drier conditions and more frequent droughts are expected.

Regional variation

The effects of climate change are felt in all the countries where Farm Africa works, affecting different regions in different ways. In Ethiopia for example, the north is expected to become significantly hotter, with rainfall levels declining, while the rest of the country could become wetter, with the largest proportional increases predicted in the driest, easternmost parts of the country.

Trends like this have a huge impact on farmers’ crop yields, which from 2030 could take a dive unless carbon emissions can be reduced significantly.

Income diversification

I was in Halaba to meet farmers engaged in a climate-smart agriculture project, where Farm Africa is helping local farmers to diversify their incomes, a measure which could help them mitigate the impact of climate change: if drought causes the failure of one crop, another may still thrive. This season some Ethiopian farmers are facing total loss of their maize, millet and chickpeas crops, while sorghum and teff are proving more resilient.

At Farm Africa we’re ever conscious of the need to balance today’s needs with resilience building for the future. Working on building up long-term, environmentally sustainable solutions that improve natural resource management might not always pay off in the short term – but will protect farmers’ long-term incomes from looming climate shocks.

In Halaba, tackling rangeland degradation and gully erosion is key – the landscape is riddled with gullies resembling mini Grand Canyons. Unless we find ways to stop the unrelenting advance of those gullies into fertile agricultural areas, farmers will lose their land and low-lying regions will become drier. Planting trees and removing livestock can slow down the process and the grass the animals will lose can be replaced with fodder crops such as pigeon-peas, Desmodium and Sesbania. By promoting the growth of cash crops such as haricot beans, which have a strong local and international market, and helping with their irrigation, we help increase production and income through agricultural intensification which doesn’t damage the environment.

Supporting pastoralists

Elsewhere in Ethiopia: in the Afar region, Farm Africa is supporting pastoralists threatened with loss of livestock on which they depend. Here the drought has all but destroyed the grass which cattle usually survive on, so we are pioneering the use of molasses sourced from local sugarcane as an alternative cattle feed.

Elsewhere in Ethiopia: in the Afar region, Farm Africa is supporting pastoralists threatened with loss of livestock on which they depend. Here the drought has all but destroyed the grass which cattle usually survive on, so we are pioneering the use of molasses sourced from local sugarcane as an alternative cattle feed.

Tackling deforestation

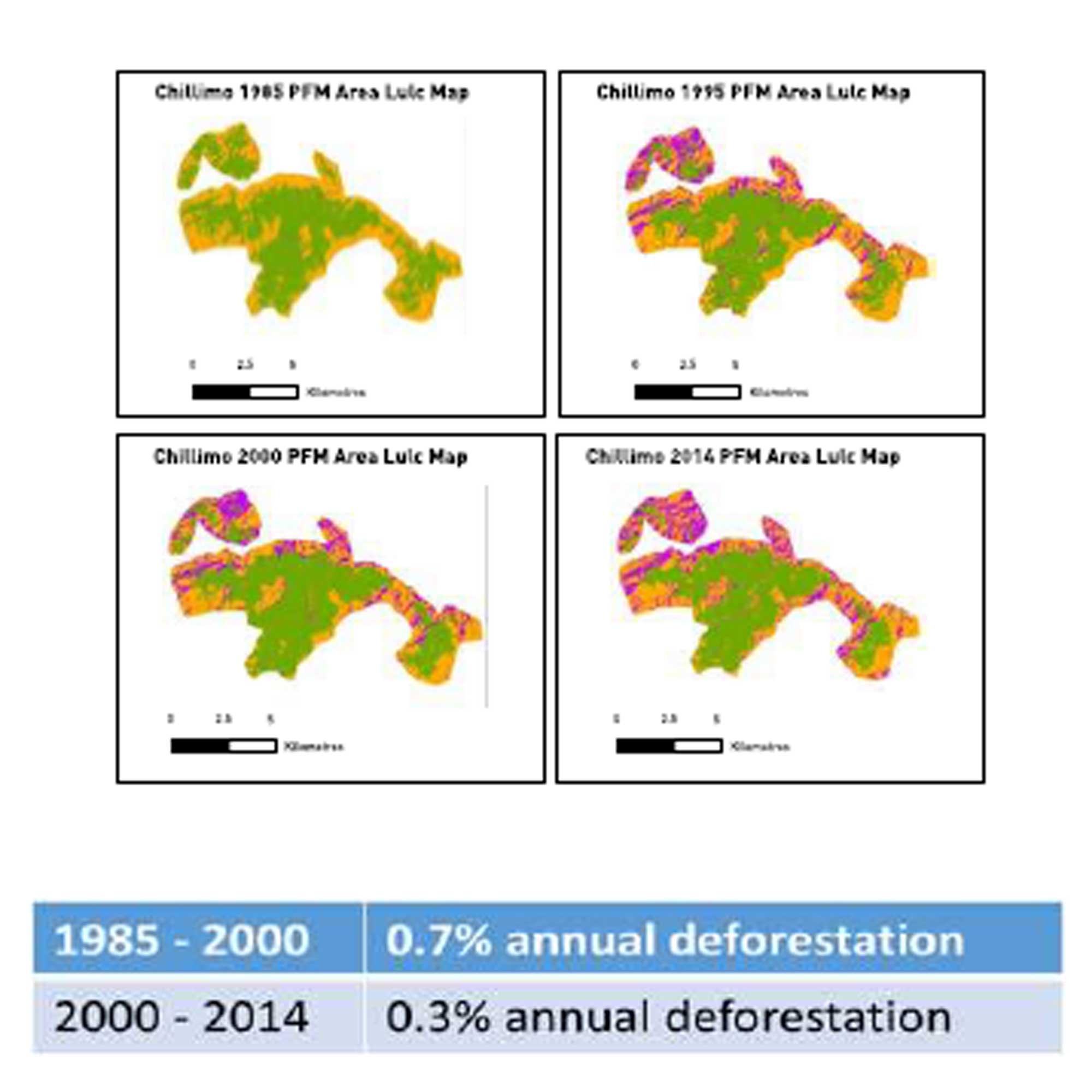

Farm Africa has worked in Ethiopian forests for over 20 years to develop Participatory Forest Management, an approach that helps local communities increase their income while at the same time slowing down deforestation. It’s an approach that works – in the Chilimo region where Farm Africa has worked since 1995, annual deforestation has fallen by over half since 2000. While a decrease from 0.7% to 0.3% in deforestation rates might sound insignificant, it can have a large impact.

The destruction of tropical forests contributes significant greenhouse gas emissions. Over the  last 12 months, with support from the Norwegian government, our team in the Ethiopia’s Bale mountains has been refining the forest management system further so that the decrease in the rates of deforestation and associated reduced emissions can be recognized under the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) scheme and provide a financial incentive for local communities.

last 12 months, with support from the Norwegian government, our team in the Ethiopia’s Bale mountains has been refining the forest management system further so that the decrease in the rates of deforestation and associated reduced emissions can be recognized under the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) scheme and provide a financial incentive for local communities.

An inspiration to us all

While the climate negotiations progress to their much anticipated conclusion, Treaty or no Treaty, the conversations around the UN buildings in Paris are very much about sharing early results of some of the concrete actions organisations like Farm Africa have been promoting worldwide. With experiences from rural Ethiopia fresh in my mind, I have been able to bring some of the climate change challenges faced by smallholder farmers in Africa to life in Paris, and also celebrate their efforts to reduce their own comparatively meagre carbon emissions: surely an inspiration to nations in the North to also commit to more concrete action to reduce their more substantial emissions.

Yvan Biot is Farm Africa’s Director of Research and Development